Although I interviewed him on April 1st — fitting, given his fun-loving personality and playful outlook on life — make no mistake, this man is no joke. I also introduce him as Kelly’s husband, who featured in our previous profile, making this a special back-to-back wife-and-husband edition. Nisheet and Kelly began their master’s degrees in completely unrelated fields in Zürich, just as I was starting mine in Geneva. What started off as a friendship at their shared apartment building, ended up in a whirlwind romance spanning the globe from the USA all the way to India with the Bugoma forest and Switzerland thrown into the mix.

Aside from being one of the funnest guys I know (I did look up whether funnest is a word and the internet seems rather torn about the subject), he is also a brainiac. If you’ve ever had the fortune of meeting Nisheet, you’ll know he’s often the sharpest mind in the room. Bear with me as I do my best to explain why — as we dive into machine learning projects, explore the world of AI, and eventually land on a startup he’s built as a side hustle.

From Chemistry to Computational Neuroscience

Nisheet’s journey into coding did not begin with a childhood obsession or a formal degree, but with something much more relatable: the need to make a bit of money during his master’s in Zürich. Programming tools such as Python and MATLAB came into the picture almost by necessity. But instead of being intimidated, Nisheet did what he’s always done — figured things out on the go. He found the right packages, tinkered around, and learned by doing, and that hands-on, problem-first approach became his entry point in the world of programming. YouTube played a huge role in his education, specifically a Dutch programmer known by his username ArjanCodes, whose clear and structured way of thinking just clicked with Nisheet.

Given his background, you might not expect Nisheet to land in a computational neuroscience lab. His master’s had been far more chemistry-focused, with his thesis exploring the use of targeted drug delivery through their release via ultrasound. Fascinating, but a reasonable distance away from computational neuroscience to make one wonder. What mattered to Prof. Alexandre Pouget, the principal investigator of the lab Nisheet joined for his PhD, wasn’t prior neuroscience experience. His main criterion for taking on a student was simple: could they have an in-depth conversation about any given topic? It was clear that he was looking for thinkers, not domain experts.

What Nisheet lacked in formal training, he made up for in logic and curiosity. He rates his programming skills at the time as a 2 out of 10, which seems low, but what he did have was a solid foundation in reasoning, and a desire to do something abstract and mathematically rich. His learning curve was steep. The jump from 2 to 4 occurred gradually, through trial and error. But going from 4 to 8 happened rapidly. Winning a PhD booster grant was a turning point which allowed him to buy more of Arjan’s courses and attend the Deep Learning and Reinforcement Learning Summer School in Montréal. That experience, paired with his determination, accelerated everything. And so, from chemistry labs to machine learning theory, Nisheet had officially crossed into the world of computational neuroscience.

From first line to long-term design

As is evident, most of his deeper coding/programming knowledge came during his PhD, which is about getting things to run. On the other hand, what he does now is better described as software engineering, which is about making sure that code keeps running, not just today, but five years from now. It’s about building something others can use, rely on, and build upon. Bridging the gap between programming and software engineering, for Nisheet, began with shifting how he thought about code. The videos of ArjanCodes once again played a key role here, which didn’t just teach syntax, but introduced principles such as how to make code future-proof, how to design with elegance and intention.

Around the same time, he came across a book from the ’90s that had a lasting impact — Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software, written by 4 software engineers collectively known as the Gang of Four (how cool is that, should we all start giving our groups rock-band-like names?). It introduced the idea that most software problems are not necessarily new, and that many can be solved using established “design patterns.” These patterns offer a way to recognise the shape of a problem and match it with a tried-and-tested solution. One example that he used to explain this concept to me is the ‘Adapter Pattern’. Imagine you’ve got a UK plug and a Swiss socket. You don’t need to rewire your home or replace the appliance — you just need an adapter. The same principle applies to code: rather than rewriting entire systems to make them compatible, you build a small bridge (or a translator) that allows each part to work as it is. It is a simple, elegant, and surprisingly powerful solution, and is exactly the kind of solution that speaks to how Nisheet thinks.

A backyard BBQ, a global challenge, and a winning hand

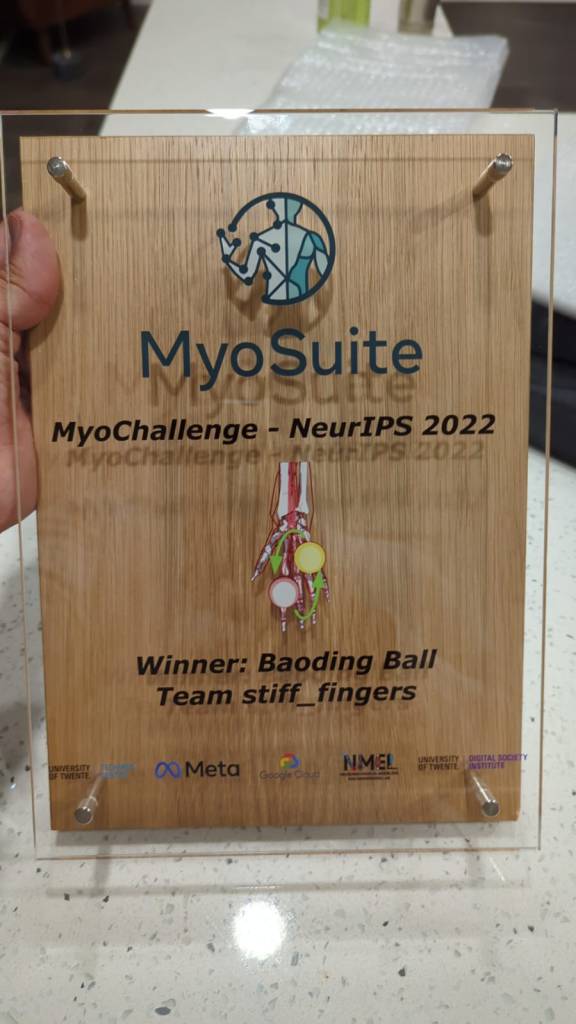

One of the projects I remember Nisheet for most vividly is also one of his coolest: a global competition called the MyoChallenge, hosted by META as part of NeurIPS — the world’s most prestigious machine learning conference. These competitions have long been a driving force behind advances in machine learning, and the best part of them is that they are open to anyone, anywhere in the world. The best teams are invited to continue into a final round with a new, modified version of the original challenge. Nisheet first heard about the challenge in the most unassuming setting: during a monthly joint lab meeting/BBQ at the Mathis’ villa — a gathering of the Pouget lab, and the labs of Alex and Mackenzie Mathis (talk about a gathering of big brains). Someone mentioned the NeurIPS competition, and the rest is history.

The year was 2022, and the challenge was as ambitious as it was fascinating: teach a physiologically realistic, muscle-based model of a human hand to move and manipulate objects with the dexterity of a real one. We’re talking about tasks that require contact, pressure, and fine motor control — things like rotating a ball in your hand, gripping, adjusting — the kind of subtle movements we barely think about but which are incredibly hard to recreate in machines. Nisheet joined forces with 2 other PhD students and 2 professors, forming a small but determined team.

The catch however, is that even his own PI, Prof. Pouget did not think they stood a chance. Competing with “the smartest people in the world,” as he put it, seemed like a stretch. And that of course became Nisheet’s biggest motivation. There’s nothing like someone telling you can’t do something to get you going is there?

They approached the task with creativity and structure, designing a training curriculum for the simulated hand, much like how you’d train your body to do a backflip: by slowly learning and experiencing every position along the way. They flew to New Orleans to meet the other top teams — a well-earned high after weeks of intense work, and a welcome distraction from a PhD project Nisheet had been struggling to feel excited about. Their method used LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) networks, which is a technique in machine learning that is particularly good at learning sequences and time-based patterns. Ironically, members from the original lab that invented LSTMs were also competing, but for some reason chose not to use LSTMs themselves. Cut to the final scene of the movie, and Nisheet’s team actually won first place!

But the story didn’t end there. He went on to turn the challenge into something more: a neuroscience publication that connected the dots between the simulation and real-world brain function. This work even landed them the cover of Neuron, a well-renowned high impact-factor journal in the field of neuroscience. From a casual BBQ conversation to international recognition — it doesn’t get more Nisheet than that.

His very own project

Using the skills he had gained across his many projects, Nisheet set his sights on something more personal. He wanted to build the tools he had always wished existed, and so decided to work on something of his own: a startup. It consists of a conference app called Axy that began not with a grand pitch deck, but with a very real and recurring frustration of navigating the organised chaos of academic conferences. Every time he and his colleagues attended conferences such as Cosyne or NeurIPS, they found themselves relying on apps that did little more than digitise the conference booklet. With thousands of posters and hundreds crammed into each session, finding what mattered — or who you wanted to meet — was a painful process of endless scrolling and guesswork. There was no personalised feed, smart recommendations or easy way to keep track of what was actually interesting.

What Nisheet wanted was simple: to wake up, open an app, and immediately see a schedule built around his interests, with no manual digging required. What we want as scientists attending a conference is to meet people working on similar problems, get feedback on our work, and discover new ideas related to our field without relying on chance hallway conversations. And so, he decided to build this solution. By April 2025, Axy has already been used at its third conference, and was one of the most useful tools at Cosyne 2025. It featured a sort of “Tinder for posters,” allowing attendees to swipe through content tailored to their interests. It let people search by topic, and created personalised agendas for each day. It even suggested a list of “poster buddies” which consisted of other attendees whose interests aligned with yours, so you could explore sessions together. You could see which talks and posters were trending, and even jobs posted at the conference were visible through the app.

There’s still more on the roadmap. Axy will soon allow users to take notes directly within the app, track trending content within specific subfields, and potentially include metadata filters like author demographics — though that introduces important questions around privacy and consent. An interactive map of the conference venue is also in the works, as well as tools for organisers, such as automated (but editable) abstract-to-reviewer assignments.

Ultimately, the vision for Axy extends beyond conferences. Nisheet wants to create a platform that supports scientists more broadly, making discovery, collaboration, and community-building easier, and he wants to keep it as free and accessible as possible. Whether that means making it open source, or using a freemium model where institutions cover the cost while users don’t pay a cent, is still under discussion. What is clear is that protecting good software ideas isn’t easy, and he is navigating the challenges of building something valuable while keeping it open to the people it’s meant to serve.

Working with the machines

Naturally after learning all that I learnt through our little interview that took place at Café Remor (an over 100 year old café with a rich history in Geneva), I had to ask Nisheet what it’s like working in machine learning at a time when AI tools are advancing faster than ever, and whether he ever feels like it might outdo him. He admits that he sometimes feels that tools like Claude can code more efficiently than he can. Still, Claude comes up short in one key area, he said: architecture — the kind of high-level, long-term thinking that good software engineering demands. You still have to tell Claude not just what the problem is, but also how you want to solve it.

He doesn’t see his job as something AI will replace. If anything, he sees himself evolving with it. The way he describes it, AI now takes care of repetitive, time-consuming tasks, which leaves him more time to focus on big-picture thinking, i.e. the high-level structure and long-term design. This process is known as “vibe coding” — where you’re not deep in the syntax anymore, but watching from above, steering the system like a conductor rather than playing every instrument yourself. And while he is realistic about AI’s limits today, he is deeply optimistic about its potential. Whatever the future looks like, you get the sense that Nisheet will be right there — figuring it out on the go, turning problems into patterns, and building the things the rest of us did not even realise we needed yet.

Leave a comment