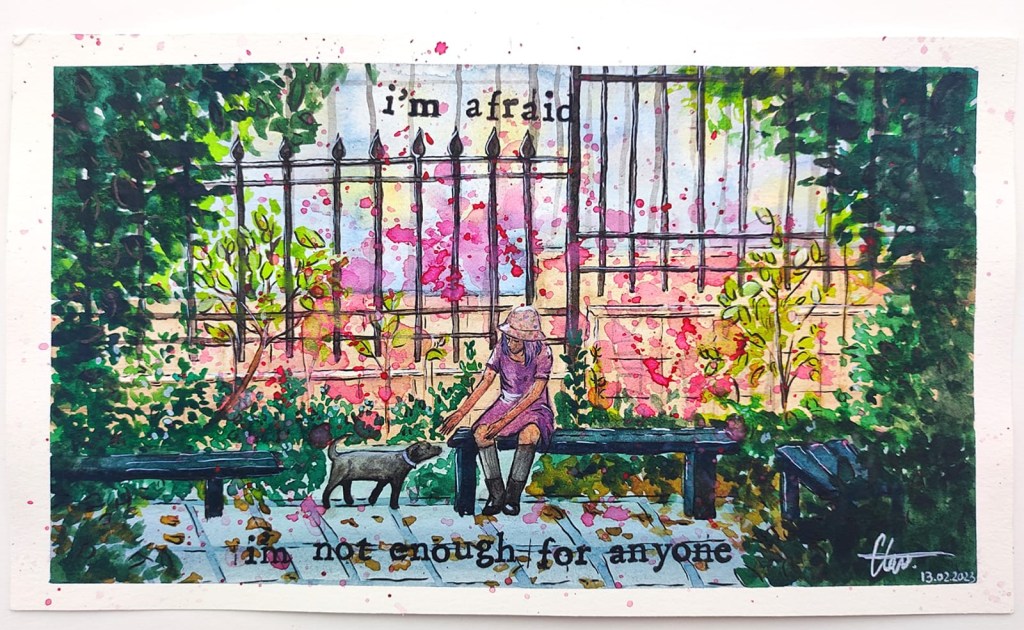

It is unbelievable to me that the subject of my next profile entered my life a mere 6 months ago. Her name is Clara. She came into my world as an intern in our lab, quiet at first, her desk looking bare and a little lonely. On a whim, I gave her a couple of my little stuffed animals to keep her company (I had more than enough). She made me some paper boats in return, and it turned into a friendship that has grown quickly and deeply. Since then, Clara has become many things to me: like a little sister, someone I talk to nearly every day even though we are far apart, and a scientist whose curiosity and persistence is inspiring. But for the purpose of this story, she is something else: an artist, and I am her biggest fan (self-proclaimed).

This article may be more like a gallery for her art (lucky us!), because to write about Clara is, in many ways, to show you the world through her sketches and colours. So let’s wander through her gallery and take a glimpse into the inner workings of her fascinating mind.

An artist in the making

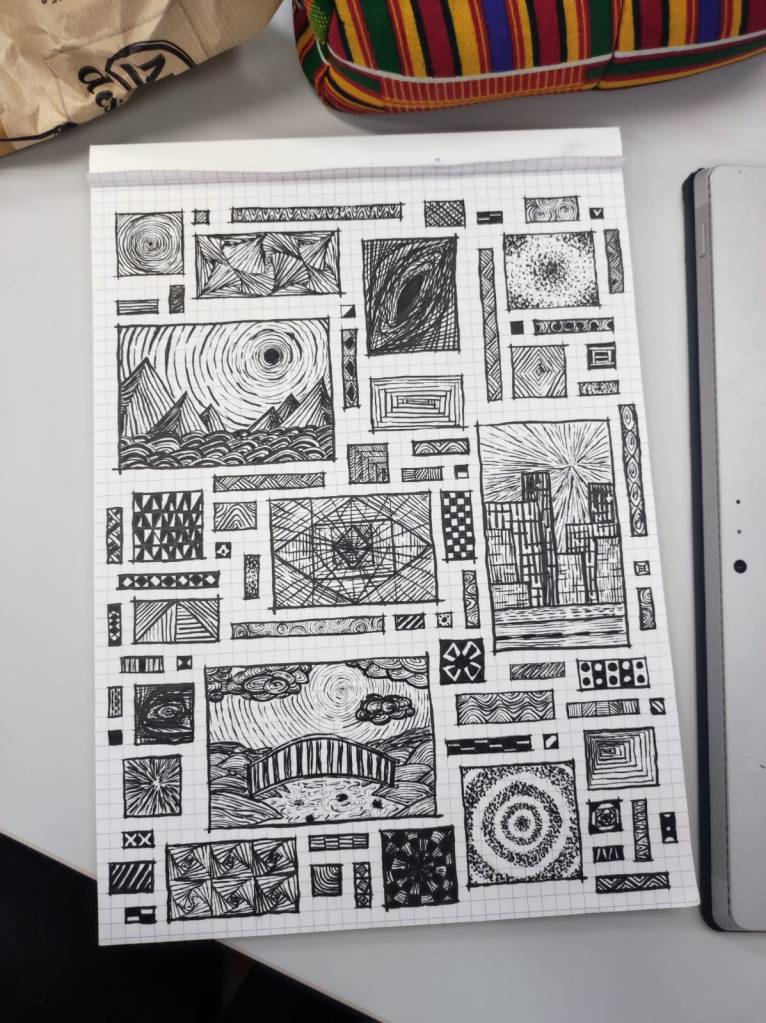

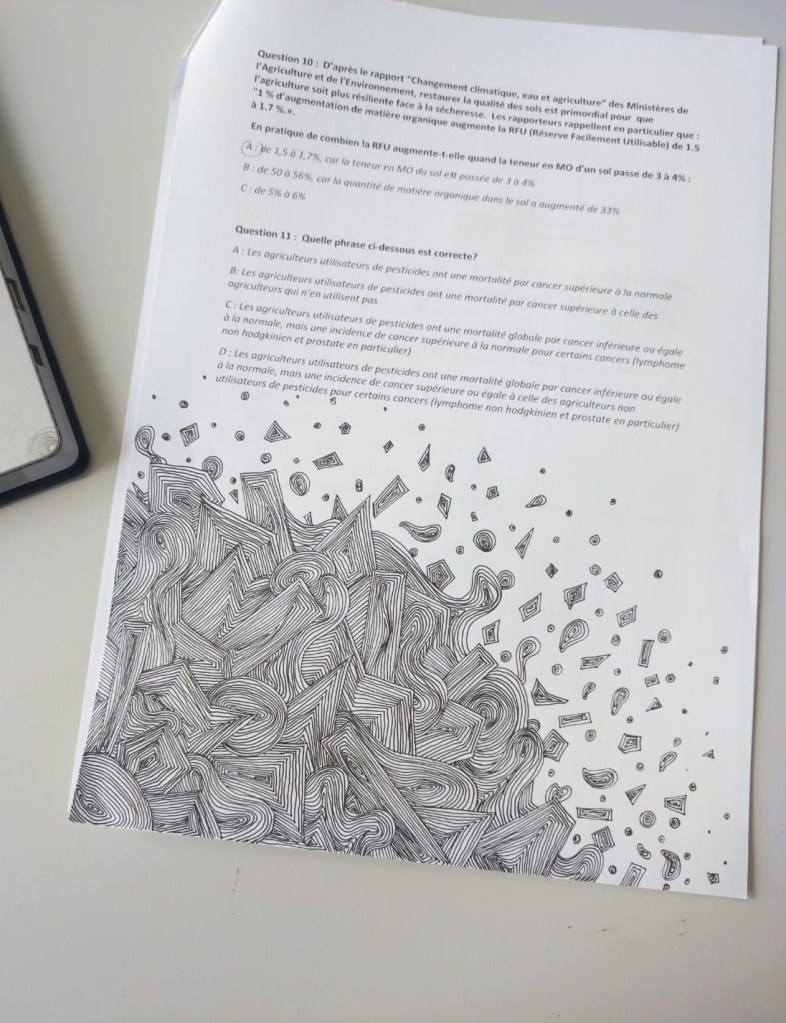

When Clara was about five years old, her mother bought her and her siblings thick painting books, encouraging them to be creative. Creativity didn’t particularly run in the family, but Clara used that book and many more to come, till the very last corner. Through middle and high school, she became an avid doodler – and judging by the margins of her notes during our lab meetings, this habit never left her.

Doodler’s delight

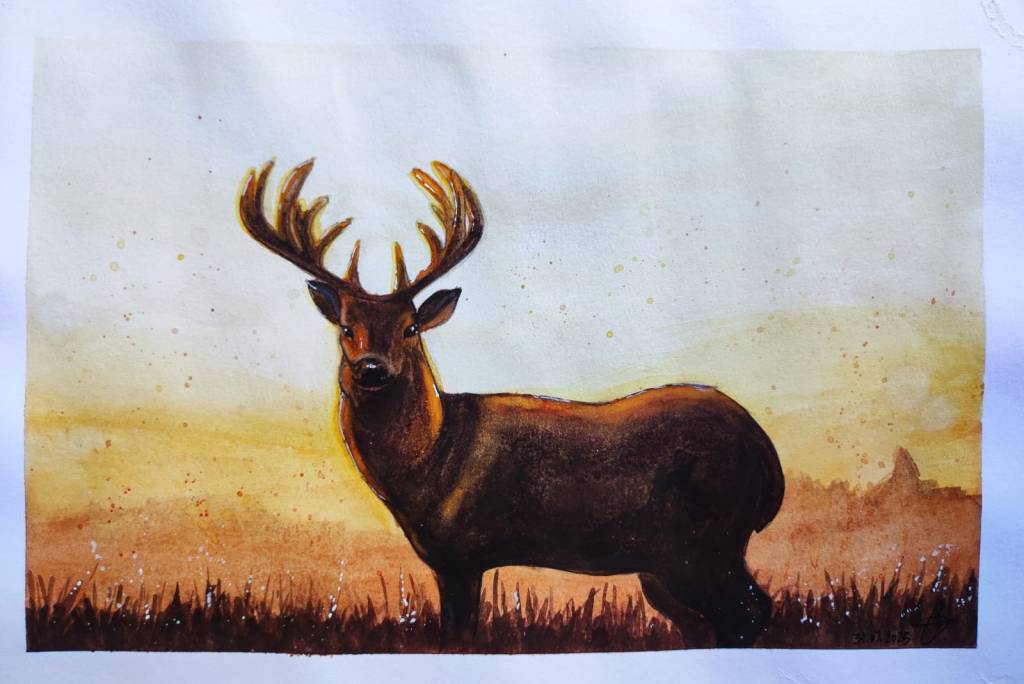

For years, drawing was something she just did, not something she thought of as “serious”. But that changed during lockdown. Instead of studying, she bought herself a palette of watercolours and started painting every single day. Around the same time, she even considered carving chess pieces out of cork – though after 3 days of blisters and numb hands, she abandoned that experiment, a little traumatized. The watercolours, however, were there to stay.

At the beginning of lockdown, she joined Inktober: a challenge that involves creating one piece a day, each based on a prompt. Soon after, a friend named Clementine sat beside her in class. Clara remembers being in awe of Clementine’s pencil portraits and asking how on earth she managed such realistic drawings. The answer was disarmingly simple: “It’s not really hard, you just look at the reference and try your best to do the same on the paper.” Clara tried it, and to her surprise, discovered she could do it too. What once felt impossibly technical suddenly became possible, and that realisation marked a turning point.

Since then, Clara has created countless pieces, most of which she gives away as gifts. Her art lives on the walls of family and friends (including mine), while she herself keeps very little. It seems fitting: for Clara, art is less about possession than about sharing beauty with others.

Alternative forms of Clara’s art: from classroom chalk to digital deer

Considerations of creating

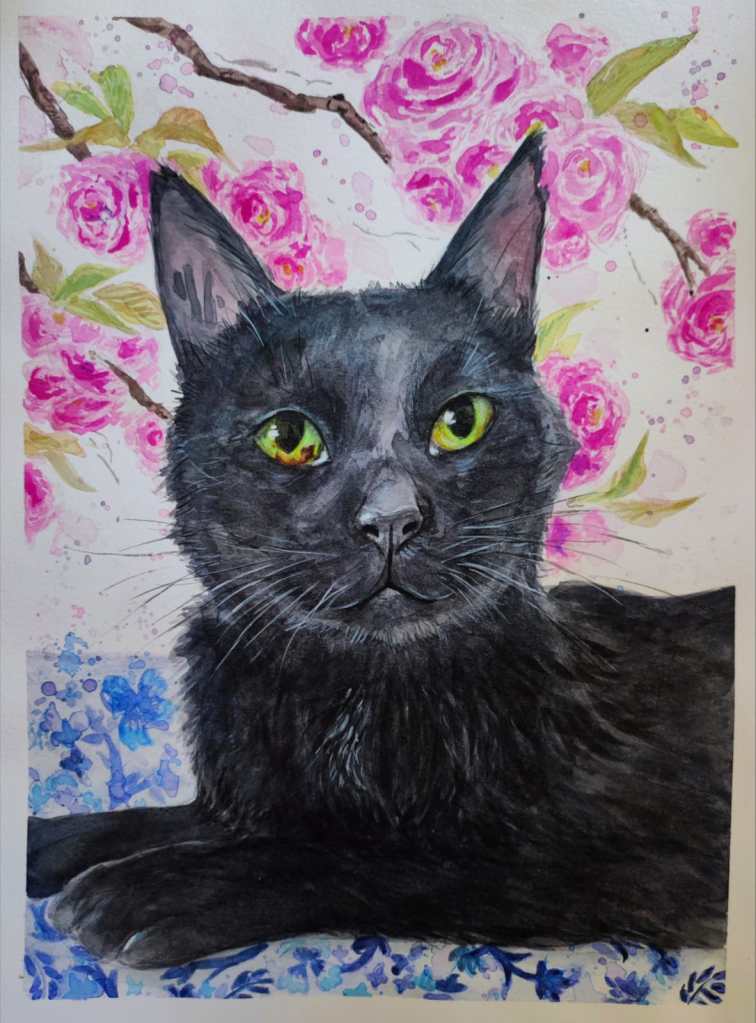

Clara rarely paints a piece in one sitting. She prefers to start and stop, letting the work unfold slowly over time. One of the hardest parts, she admits, is knowing when to stop: she can go on endlessly, adding more and more layers. And with watercolours, there is little room for hesitation. Unlike acrylics, you can’t just paint over a mistake – you have to commit.

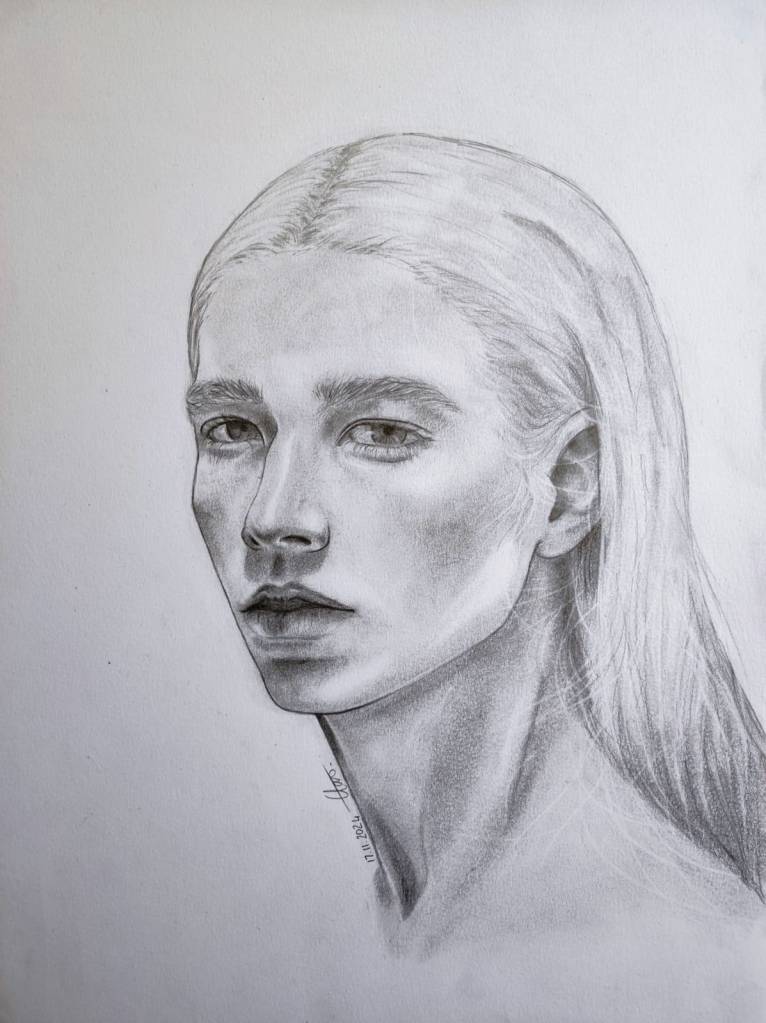

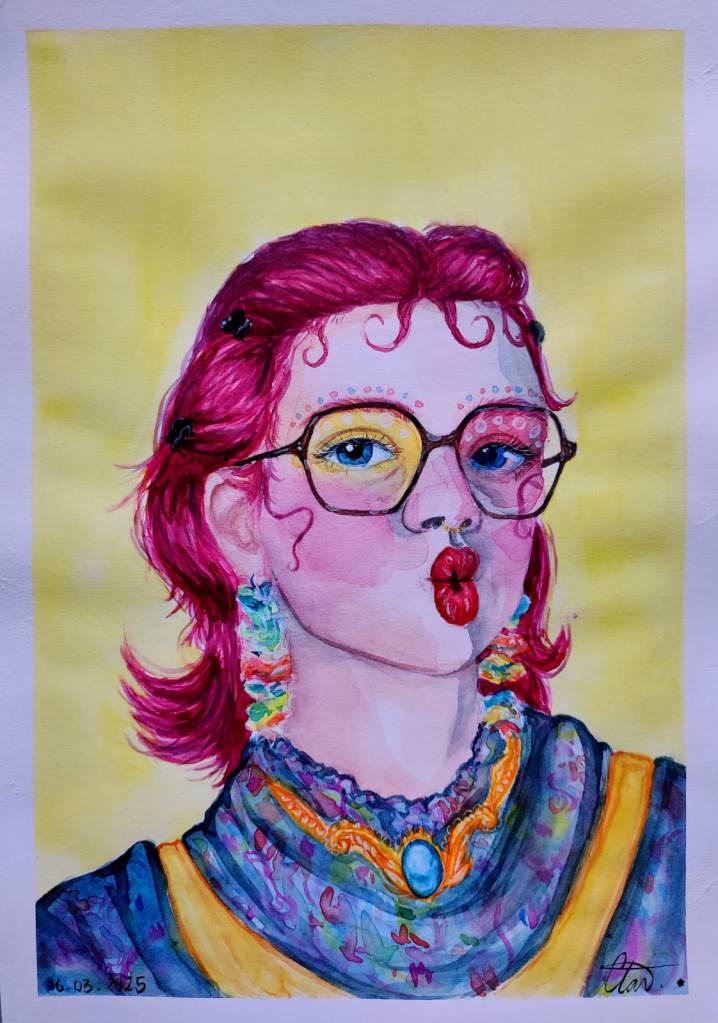

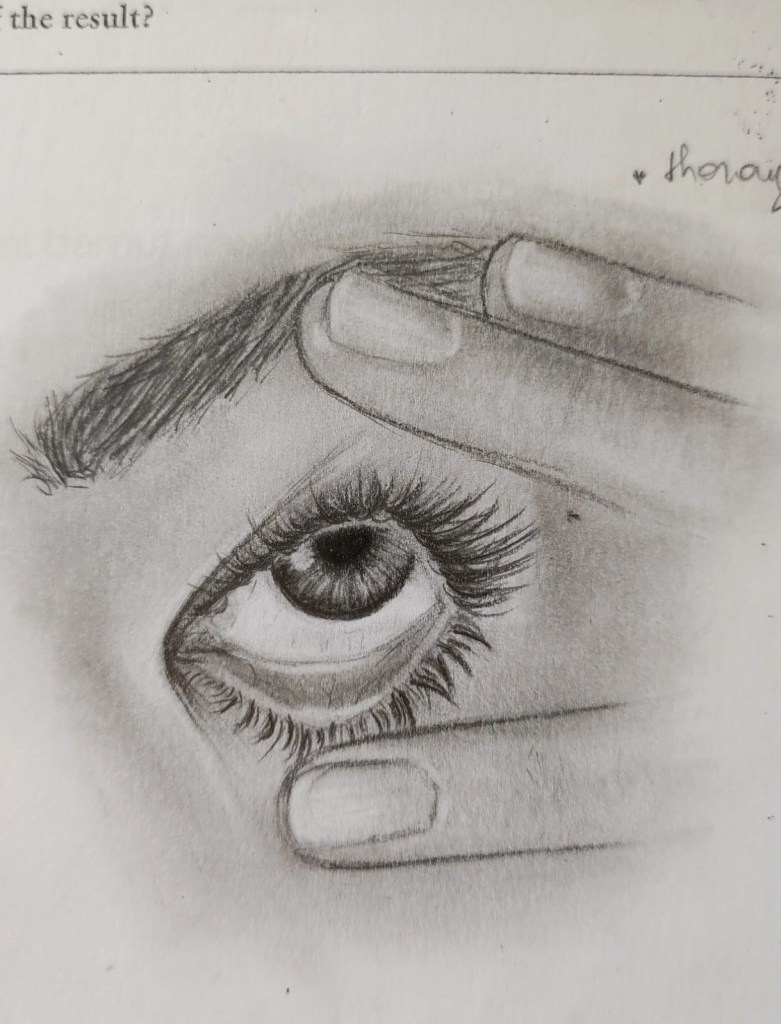

She reflected with me on the uncertainty of not knowing the “right” order of things – shading first or colour first? She admits she is still figuring it out, and that constant learning is part of what keeps painting alive for her. Still, the toughest and most time-consuming works remain graphite portraits, some of which have taken her up to 30 hours to finish.

Watercolours, though, are where she feels most free. They let her play: choosing the amount of paint, the amount of water, layering, and deciding whether to wait for one layer to dry or to dive straight in, knowing the outcome will be entirely different. They are less rigid, less accurate than the reference, and that imprecision is part of the joy.

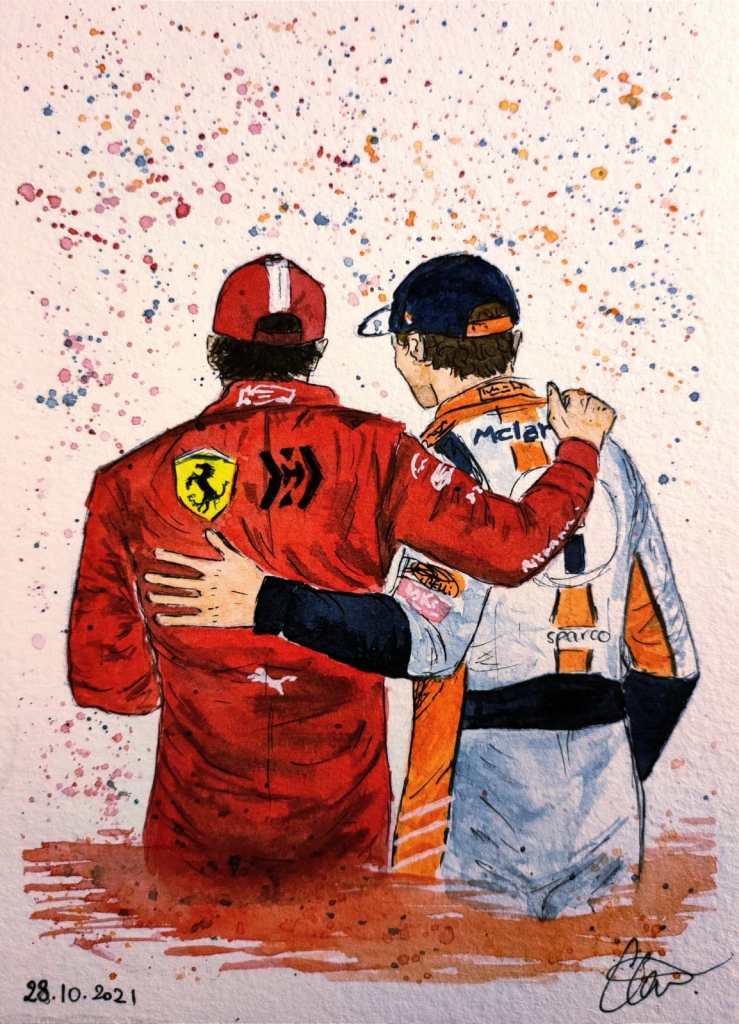

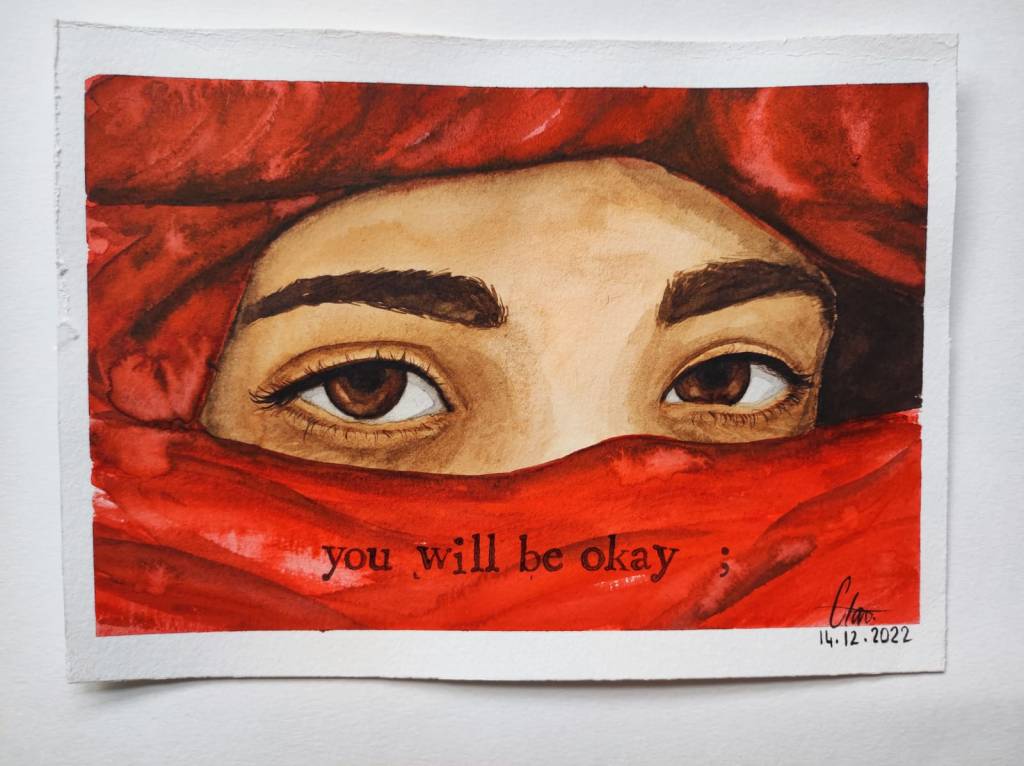

Portraits using 1) alcohol markers 2) graphite 3) watercolour 4) digital

By contrast, she described her limited experience with oil painting as the opposite: deliberate, premeditated, a medium that requires careful planning before the first brushstroke. And then there are the ideas she hasn’t yet had time for, like wood sculpting. She jokes that her problem is the sheer lack of hours in a day to try everything she’d like to. How can anyone say they’re bored?

Serendipity on paper

Clara’s sketchbooks are alive with variety when it comes to techniques and subjects. Bursts of colour, delicate graphite lines, experiments in light and shadow. At one point, she even painted Formula 1 cars and drivers – not because she followed the races, but because a friend did, and she wanted to make her a gift. The paintings were joyful, bright, and full of motion, their speed almost visible in the brushstrokes. And in the process of making them, she became a fan herself. How cute is it that art opened the door to a new world, and the gift she created ended up giving something back to her too.

She also loves the challenge of drawing in negative which involves an inversion of tones. What should be bright, she makes dark; what should be dark, she leaves white. The effect is striking, like looking at a photograph passed through a negative filter, where light and shadow swap places. And then there are the eyes. Clara has a way of capturing them with uncanny precision, so that her portraits look back at you as if alive.

Drawing in negative

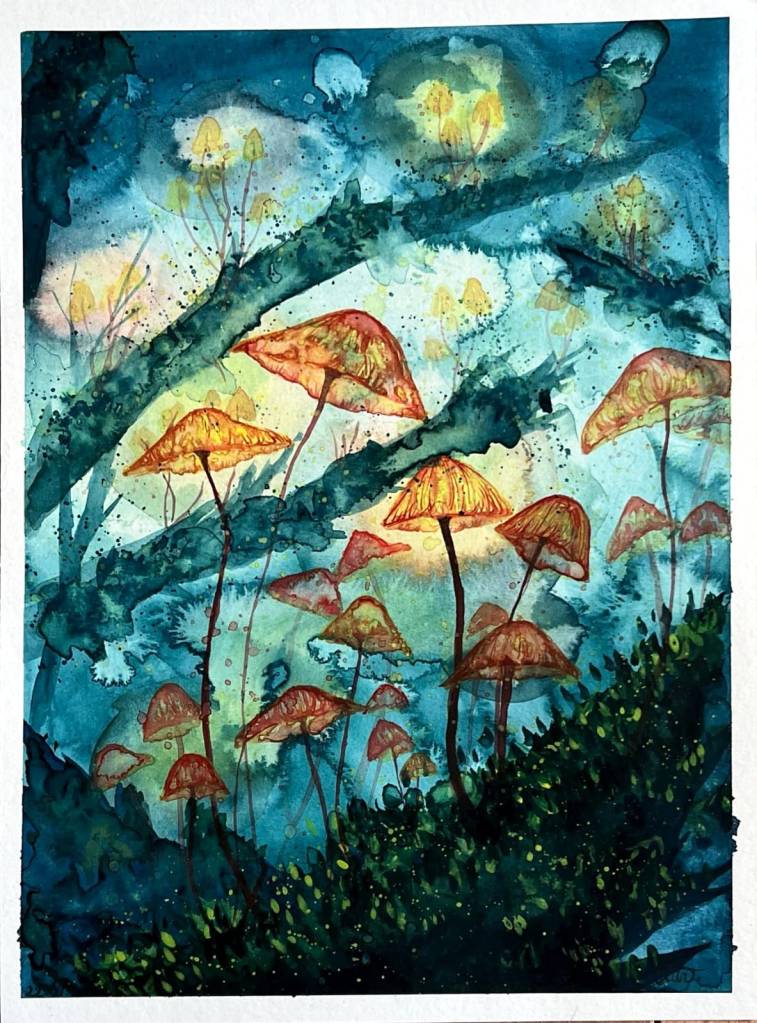

But when asked about her favourite piece, Clara hesitated. “My favourite is yet to be created,” she says. Still, if you twist her arm for an answer (what a dark phrase; did people really used to do that?), she would choose an older piece of work. One she began with no plan and no clear vision. Somehow, it unfolded into something striking. The result was a dreamlike watercolor of glowing mushrooms, their amber caps lit from within like lanterns in an enchanted forest. The background awash with deep blues and greens, a tangle of shadow and light, as though you’ve stumbled into a secret world after rain. Clara painted it with no plan, no clear vision; simply letting the colours bleed into one another and guide her hand. Somehow, it unfolded into something striking. She thinks it turned out beautifully precisely because she didn’t know where it was going. Less pressure, more freedom, and a perfect definition of the word serendipity.

Clara never trashes the work she doesn’t like because she doesn’t see them as failures, but as lessons. Each one carries a learning, a practice stroke on her way to the next. And in between those lessons, she is (quite literally) always drawing.

An artist without a mind’s eye

What makes this even more remarkable is the way she draws. A chance conversation over lunch one day revealed that Clara has aphantasia. Aphantasia is a term used for the inability to form mental images. People with aphantasia cannot summon pictures in their “mind’s eye,” even though they can describe, know, and understand what something looks like. It is estimated that fewer than 4% of people experience it, making it both uncommon and often unnoticed. At the other end of the spectrum lies hyperphantasia: a mind capable of producing vivid, detailed imagery. Both exist along a spectrum, but the contrast between us was striking.

One afternoon at lunch in the lab, a colleague mentioned a podcast she had listened to about aphantasia. It was one of those offhand conversations that end up changing how you see someone. That day, Clara discovered she had it. I, on the other hand, realised I might be her opposite, with a potential case of hyperphantasia.

It is a fascinating paradox: one of the most talented artists I know cannot actually “see” what she paints in her mind’s eye. But what is a mind’s eye, anyway? Here we drift toward the philosophical. Clara explains it like this: if you tell her to imagine something, she doesn’t see it. She knows it, but she doesn’t picture it. “It’s like when you talk,” she says. “You don’t have to imagine the words before saying them. You just say them.”

Even though she cannot visualise her drawings before they exist on paper, she knows what they should look like. For most pieces, she works from a reference like a photo, an object or a person in front of her. Only a few things she can draw without one, like eyes, which she knows so well they come easily. She wonders if her aphantasia even sharpens her focus: since she cannot be distracted by an imagined version, she must attend closely to what’s actually in front of her.

When I asked her to explain how the phenomenon felt (I admit this is a tough ask), she described it like working with a ghost: something she knows is there but cannot quite see. Sometimes, she catches a flicker like the edge of an image in her mind’s eye, but it quickly slips away.

The gift of making

Clara’s list of things she wants to paint grows faster than she can keep up with; so fast that older ideas fall away before she ever reaches them. Her current project is a gift for a friend: a scene from a video game called ‘Red Dead Redemption’. Like much of her work, it is born of inspiration and shaped by generosity. She never paints just for the final result. “You have to feel the inspiration,” she says. “If you like it enough, you’ll learn what you need along the way. It’s more about the process.”

The same spirit runs through her other creations, like the little crocheted animals she made for each person in the lab before leaving. She only began crocheting two or three years ago, again with a gift for a friend: a cow (and she still only makes them to give away). Even the stuffing is resourceful, coming from the toys her dog Bisha destroys.

Sometimes I wonder how she has ever passed her exams, since she always seems to be painting and drawing rather than studying. But I’m grateful she does what she does, because one of Clara’s pieces is worth more than any of the words I could write.

————————————————————————————-

A small note about aphantasia for those who might be as curious as I was:

Turns out that some of the very talented artists/animators we know have aphantasia including:

- Ed Catmull – co-founder of Pixar

- Glen Keane – animator behind Ariel in the The Little Mermaid – he worked on movies like Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin and Tarzan

- Clara

The word itself comes from Greek: “a-” meaning without, and “phantasia” meaning imagination or appearance. If you would like to listen to the podcast episode that sparked this whole conversation, you can find it here.

Leave a comment